When young people protest on the street and tell us that we are destroying their future due to our failure to act on climate change, we know we have really ignored all the signs. Who cares about climate change? We are numb to the issue because we are daunted by its size and extent. We can’t seem face it and business as usual rolls on. It’s time to call it out: a climate crisis. What has this got to do with landscape architects? We cannot continue to put parsley on the pig because shortly the pig will be burning.

Scientists say that unless we drastically draw down carbon in the next twelve years, our ecologies and cities will bear the exponential grunt of up to two degrees of climate led disruption. It dawned on me that twelve years is the timeframe that my current planning projects are likely to reach fruition: this means I am effectively facing this design challenge right now. When I look more closely, it appears that many of my existing landscapes may not survive 2 degrees…what role will landscape architects like me play in helping stave off the ecological and social crisis arising from 2 degrees temperature change?

If we need to become alarmed about climate change, the article The Uninhabitable Earth is a good start.

If we want to see what our lifestyle changes do to the imminent barometer rise, test the climate calculator. If we want to know whether minor tweaking is required to our professional work, or whether it’s a deep adaptation, read Professor Jed Blundell’s article in Scientists Warning. Blundell outlines that we need to plan not just for climate adaptation but also for disaster risk reduction, and within the next ten years:

“…recent research suggests that human societies will experience disruptions to their basic functioning within less than ten years due to climate stress. Such disruptions include increased levels of malnutrition, starvation, disease, civil conflict and war – and will not avoid affluent nations. This situation makes redundant the reformist[2] approach to sustainable development and related fields of corporate sustainability. Instead, a new approach which explores how to reduce harm and not make matters worse is important to develop. In support of that challenging, and ultimately personal process, understanding a ‘deep adaptation agenda’ may be useful.”

Business as usual is over. Given our failures to meet all the climate targets to date, this week is when I really need to start designing for 2 degrees, so my landscapes will still be around in 2030. We need to stop worrying so much about image and worry more about building within a climate crisis as if our lives depended on it: within future habitats where humans, plants and animals still actually coexist in the future landscape. We have to transition to cities and infrastructures made locally and from fully recycled materials; where we plant for shifting ecologies, embracing the spectrums of drought/heat and storms/floods; Where climate, water, energy, waste, food and soil are the primary drivers of design.

AILA provides a good framework for us to build climate change resilience, but it’s time for each of us to move beyond reading policy and to ramp up the deep adaptation action. We will need to move many future communities to safer landscapes and begin the difficult transition away from current at- risk places and cities. A national settlement strategy will be required as many towns and places become at risk or uninhabitable due primarily to heat, lack of water and flooding. We may also need a national local food strategy as import systems may break down and food production collapses in various parts of the world. We need these strategies now in order to plan for the next ten to twenty years. After this, it’s likely that it will become a military problem related to sovereign risk and protection.

Extinction rebellion protest in Brisbane, May 2019

Flooding of my West End neighbourhood in 2011

Flooding of my friend’s street in 2011

Flooding near my South Brisbane office in 2011

A landmark UN report this May called for ‘transformative change’ as a million species risk extinction. This transformational change is essentially the deep adaptation agenda suggested by Blundell reaching mainstream world governance on biodiversity. The study concludes that biodiversity loss and climate change feed off each other in a vicious circle and that we have to save and create habitat in the process of also drawing down carbon within the world. Conventional food and forestry landscapes may draw down carbon but will not also help to preserve the biodiversity which ecosystems rely on and which keep humans alive. As the world population grows, we continue to destroy our ecology, which is as big a risk as climate change.

As George Monbiot the environmentalist argues, no one is going to save us: government and industry are moving much slower than the environmental and climate changes that are occurring. We have to help mobilise our communities. We have to change our professional focus and change it fast. Monbiot notes that ‘a recent estimate suggests that around one third of the greenhouse gas mitigation required between now and 2030 can be provided by carbon drawdown through natural climate solutions’. The study suggests that about 37 percent of the carbon drawdown could be achieved through natural landscape-based solutions involving ecologically driven design and restoration. This is within the sphere of landscape architects and planners: massive inputs of natural reafforestation, forest conservation and environmental habitat rehabilitation to draw down carbon are actions we can lead on. The 20 landscapes compared for climate mitigation potential in the study referred to by Monbiot show that we have to start collaborating heavily with agronomists and ecologists if we are to be a part of this deep adaptation.

Of the 80 climate mitigation actions analysed by dozens of scientists in Drawdown, a third are actions which landscape architects can assist or lead on. Again, we will need to arm ourselves with much better skills and knowledge in the planning and building of resilient food and forest landscapes, as well as train ourselves in water, waste, energy and heat systems.

Things we can do

Hiding is not an answer. Neither is denial. Acting to achieve climate adaptation through the power of planning and design are things you and I can do. Like many others who have delved into 2 degrees, I find there is a temptation to become despondent, and to want to sell all my assets and go to Patagonia or New Zealand and hide in a transition farm in the forest! But this helps no-one else… so the things that I can act on most effectively in the next ten years relate to my ongoing community work and long- term projects.

For my part, I have decided to transition to a practice of 3 days a week, to leave time for me to help my local community transition around climate change in the next generation. My partner and I have worked in landscape architecture for generations: It’s time to transition our practice and work on climate change projects as a priority. To do this, we will scale back on other works to make time to research, to lobby and to act on these deep adaptation challenges. It makes sense that we focus on projects that are already planned and able to be implemented in the next ten years.

Local and community projects I will focus on

1. Implement community action plans

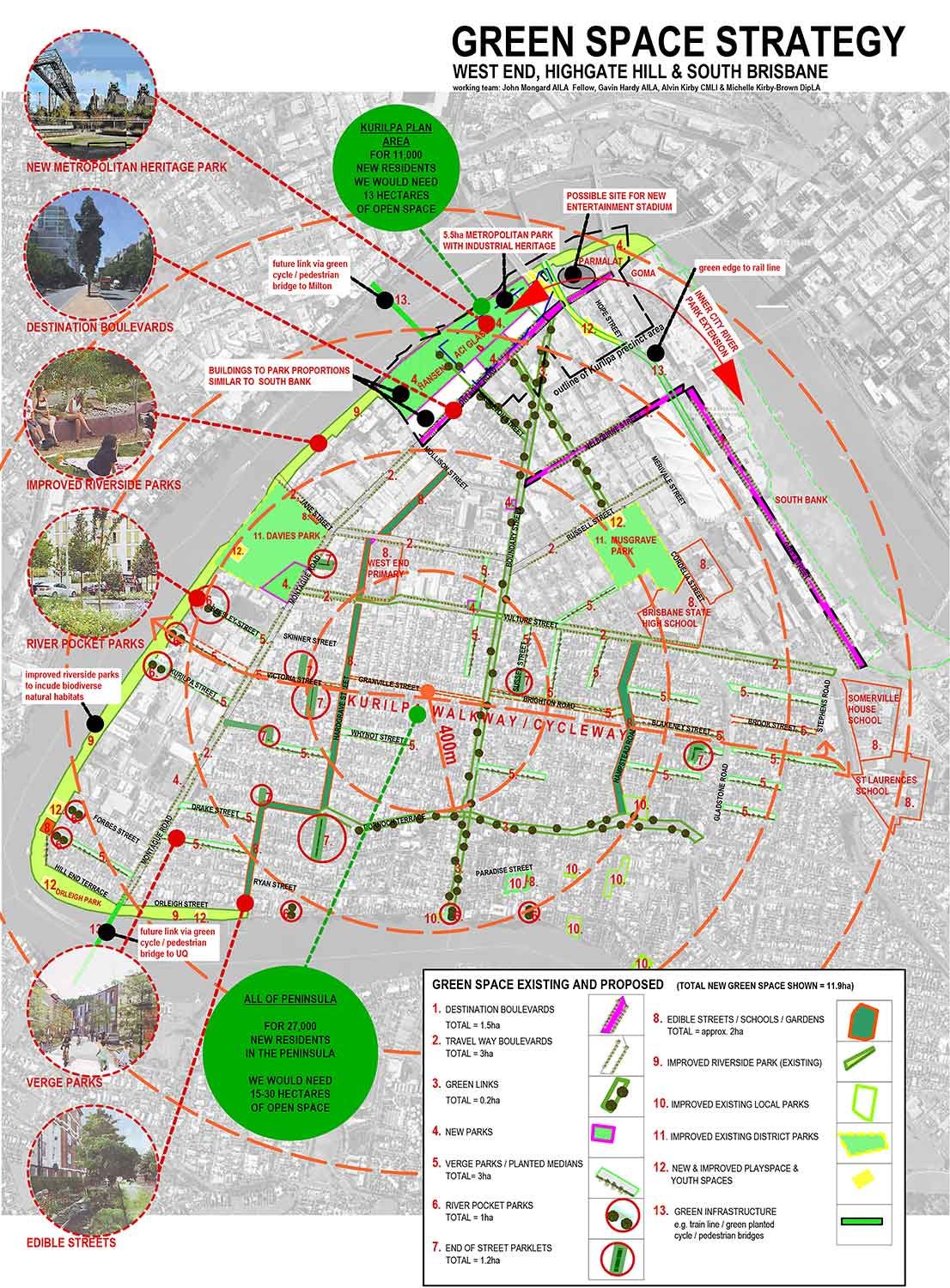

Help implement community action plans already in place in my neighbourhood. The Greenspace Strategy by the West End local community identifies 11 Ha of greenspace that can be reclaimed in the existing commons. We can ramp up community action on this to reduce urban heat and draw down carbon locally in the next ten years. Greenspace strategies like this could easily be led by landscape architects working in each local district with their communities. Mobilise your friends and colleagues within your local neighbourhood: create local resilience projects and actions, make a community action plan.

West End main street: The large tree was planted in the middle of the road in 1995 through a community design project and now creates its own microclimate after over twenty years.

The Greenspace Strategy: the local community found 11 hectares of crown land that could be greenspace and biodiversity areas in their neighbourhood.

Tactical urbanism: the community activating a future park space.

West End greenspace: Bunyapa Park is a new park lobbied for and designed by the community.

2. Design and build forests and rewilding areas

The Living Classroom project in Bingara, NSW diverts flood water catchment into three kilometres of biodiversity forest around a chain of lakes and billabongs. I will help continue this reafforestation and permaculture farm.

3. Create and rehabilitate local waterways

Identify gullies, parks and wasted spaces that you can reclaim and rehabilitate in your neighbourhood. The Local community in West end identified 12 potential new parks to reclaim in unutilized crown gully lands. I will help create these green spaces.

4. Build farms and food gardens

Reclaim unused verges and parks with community run projects. Jane Street community garden in West End is on a street verge and is run by a not- for profit association supporting local gardeners. It reclaims about 1000m2 of area that was not being used.

5. Plant street verges to create habitat and reduce heat

Plant out verges in your neighbourhood with your neighbours, schools and community groups. Kurilpa Futures community group in West End is building verge gardens with local residents.

6. Plan ahead for flooding

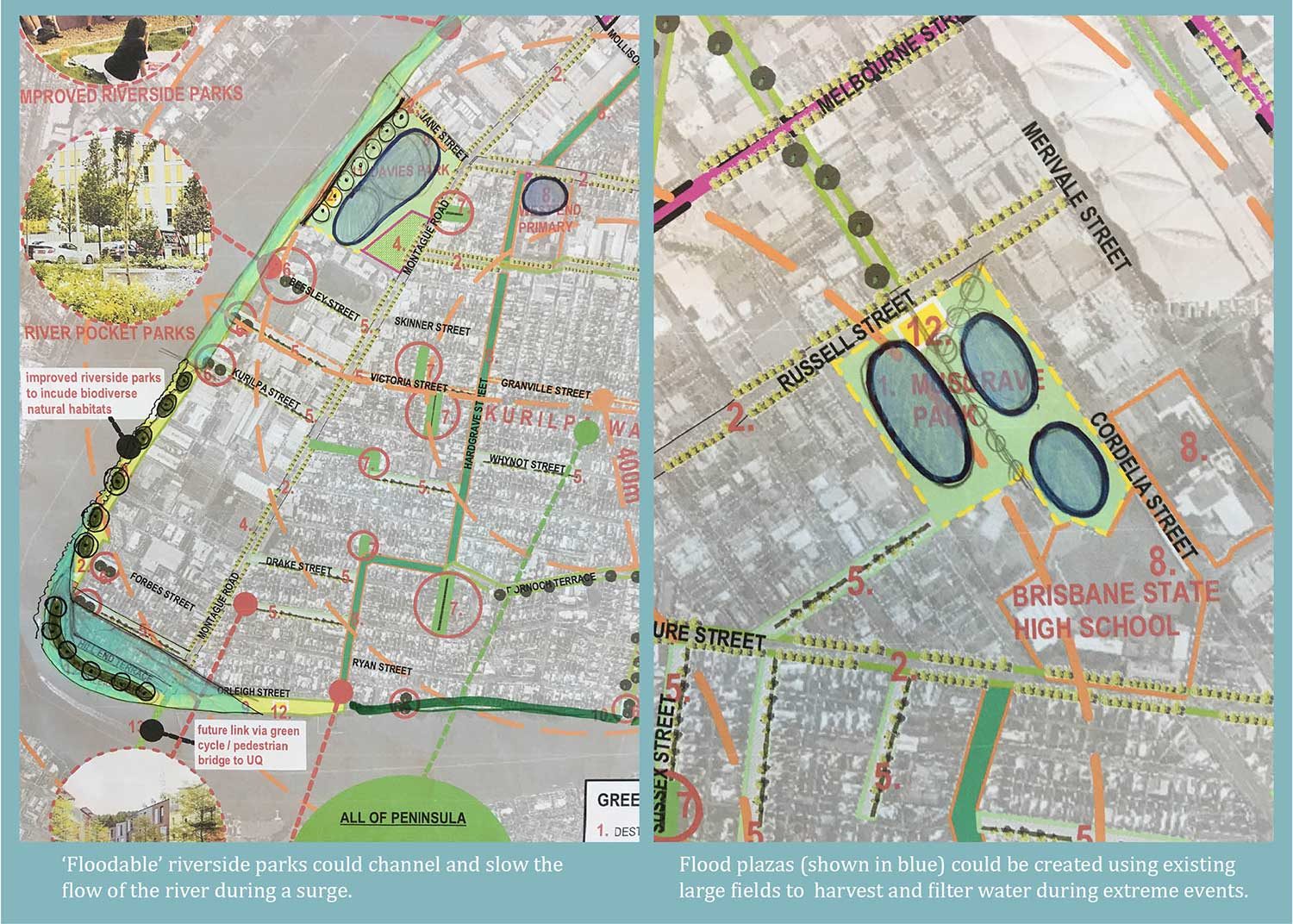

My neighbourhood of West End flooded in 2011 and will substantially flood with 2 degrees. Flooding strategies can be enacted with strong government intervention to transition areas and sites. The Blue Strategy in the Greenspace Plan identifies ideas for at risk areas to manage flooding locally in the West End peninsula.

7. Plan and build locally sustainable food and farms

The Tweed Shire Sustainable Agriculture Strategy refocuses a productive region back toward a closed loop food system. Build a farm: the Charleville date farm was built by volunteer pastors, a family and some helpers. It recycles all the towns wastewater and produced its first date crop after five years, all within a degraded desert landscape. Help rural communities who need it most.

Local group Kurilpa Futures ran a community workshop which identified urban forests and urban sponge parks as a community priority in renewal of industrial lands in West End.

Blue Green strategy: the local community identifying strategies to deal with climate change and flooding.

West End verges: five neighbours reclaiming over 200 m2 of street verge, creating shade and habitat.

West End verges: Kurilpa Futures community group and Tangara Retirement Village residents planting street verges.

8. Lobby hard for a national resilience framework

Lobby hard for a national resilience framework, a deep adaptation agenda: to create program, funds and resources to deal with progressive climate change impacts. Make climate change the driving criteria in my projects: Landscape architecture will need to transform itself toward essential living infrastructure: a shift from amenity to survival priorities.

9. Push for urgent policy change

I will push for urgent policy change and immediate action in all layers of government. I will join Extinction Rebellion.

10. Change my lifestyle

Change my lifestyle: eat less meat, fly and drive less, buy local, don’t waste.

We can’t afford to tinker at the edges. We are being called to act in many more landscapes than those focused on amenity: It’s a call to arms to prevent imminent ecological and climate collapse within our lifetime. What can each of us contribute?

Charleville Date Farm: recycles all the towns wastewater through a wetland system.

Charleville Date Farm: creates a food source and local work within a desert landscape.

Charleville Date Farm: rehabilitates waterways to encourage bird and wildlife habitat.

Charleville Date Farm: over 200 date palms have been planted in stage one.