The forces of change in our society are increasingly globalised and franchised. Investment, trade and even the way we relate to each other in our living places are being shaped by patterns and pressures which are beyond our view. As we continue with the rapid expansion of our cities, long-term fault-lines are being built into the social and urban structure of our Australian places. Our suburban way of life is moving us toward an entropy with no sustainable future.

The forces of migration, coupled with moneyed ageing and gentrification are proving a potent elixir for new growth. It seems to be happening quicker than we can think: No time to reflect. Just Do It.

The great American dream continues to be rolled out into the suburbs of the globe, with the recent addition of a few environmental gestures to lakes and swales. Are we contributing to the death of difference in our urban places? We can’t seem to get beneath the skin of this suburban thing to change it into other typologies relevant to our sustainable visions. Is there no other new way of living in areas of new growth?

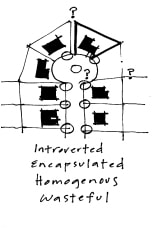

Obese America, tranquillized and secure in its gated communities, is perhaps not the ideal model for the new world, yet the globalising forces shaped by corporate America are merging us toward a template society of like-minded consumers, living in urban products which lack variety, sustainability and relevance to the increasingly complex society we live in. Landscape architecture desperately needs historical critique, and built precedents relating to new and more sustainable urban and suburban forms. A contemporary philosophy which connects landscape, urbanism and infrastructure design is needed to drive landscape architecture into a more central position in the development world. This philosophy could be centred around participatory design, planning and economic processes. Building, thinking and dwelling would be inextricably linked in the design process (Heidegger, 1975. p.160-161). All participants in the place making process would be engaged as a community of potential dwellers. This will require designers to place themselves in the role of dwellers as they respond to specific people and landscapes. The practice of placemaking would shift ‘from what things are, how they function, and what they look like, to what they do’ (Fry, 1999, p.289. The production of private and public landscapes and places would move us toward a more participatory economic system, where ‘goods with substancial collective impact are handled by social deliberations that arrive at choices that try to appropriately incorporate the wills of the people affected, to massage and modify proposals so they become optimal, and to apportion payment for them in accordance with the benefits they bestow, and when need be, to correct for negative implications or make restitution for them’ (Albert, 2003, p.143).

This paper analyses the current model of creating suburbs, and offers two case studies of alternative models for a more sustainable way of facilitating living places utilizing types of participatory processes as outlined above. These case studies are of hinterland communities faced with growth and are offered as examples of what Tony Fry (1999, p.290) refers to as ‘redirective practices’ that turn against the unsustainable in the search for sustain-ability.

The suburb with the big box model

In the 1980’s I began my career by assisting a town planner in developing a large shopping mall on the edge of an emerging town in South East Queensland. Fifteen years later, I came back to the city to try to reinstate local village qualities, which had been progressively rubbed out by strip development in all the wrong places. By this time, the structural damage was done and the remaking of the local proved costly. Smaller gestures of patternmaking could be instigated, but the placemaking battles were lost: coastal village life was sucked into dislocating shopping malls and suburban cul-de-sacs, lost to the walker forever.

This proved to be a repetitive blueprint, the dominant urban design model right up to this day in Australia. The momentum of the franchised retail box sitting in a homogenous suburban fabric, designed for the mythical average family with two cars and two children has not abated.

Even as the tide changed in Australia in the mid-1980’s, with the shocking realisation that we had a climate which could support communal living on our main streets and in our urban places, the global retail and suburban model makers absorbed this wave of celebration of the footpath, and branded themselves villages also. Could these really become the meaningful public realms of our postmodern future? We tended to give them the benefit of the doubt, and ended up with huge insulated machines for consumption, such as ‘Garden’ City, Pacific ‘Fair’ or Indooroopilly Shopping ‘town’. These so called centres dominate a homogenous suburban fabric with instant names based on forests, pines and lakes, and boasting themselves as communities and villages. The most economically efficient way to exchange goods did not prove to be the most environmental or social model in the suburbs. The consumerist model of success required people to have cars and money to participate effectively in this suburban dream, and so it has been individual material wealth rather than any notion of building communities which has driven the development machine.

Community / Suburb

The idea of fostering a sense of community in ‘subdivision’ design has been to date mostly a marketing exercise. The elements which foster and engage a community are treated as extras in these developments: seating, public open space, streets, plazas and free community venues such as halls and recreation areas. The philosophical paths of urban planning, environmental design and community development are yet to effectively merge in the suburbs.

“Intentional community” is a term describing a more purposeful way of planning places for living (Kelly and Sewell, 1996, p.102-105). It implies that making community is an urban process as well as an urban form, and that future dwellers need to be actively involved in both. Freire (1993, p.160-164) would call this a social-change process where the future dwellers are part of a process within which they build their own view of their future, beginning with the circumstances of their everyday life.

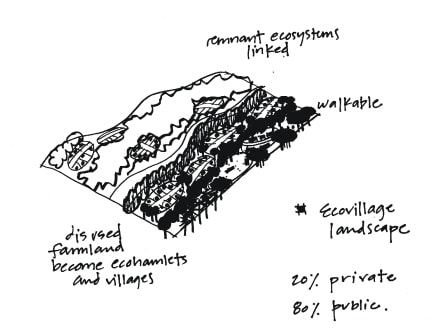

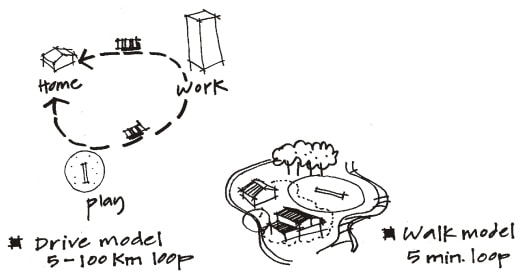

An ecovillage is a new urban form which capitalizes on the sustainable principles which have been inspired by the Permaculture movement and makes an overt objective to facilitate intentional community. There is no definitive text on ecovillages since they are an emerging form with few formal or built precedents, but they form part of a body of thinking emerging on the World Wide Web around ecological forms of living. Ecovillages also draw inspiration from alternative lifestyle movements calling for better energy usage, more community life and a greater nexus between work, play and living areas. The walkable neighbourhood is at the heart of Ecovillage planning (Figure 1), as is the conservation of landscape and biodiversity values. Ecovillages differ from current new urbanism forms through their strong environmental and sociological centeredness and through their landscape/infrastructure fusion. They offer a different level of density which feels rural or landscape oriented but still provides a communal centre. This centre may vary in its uses and functions but should aim to provide as many home/work/play networks as are possible.

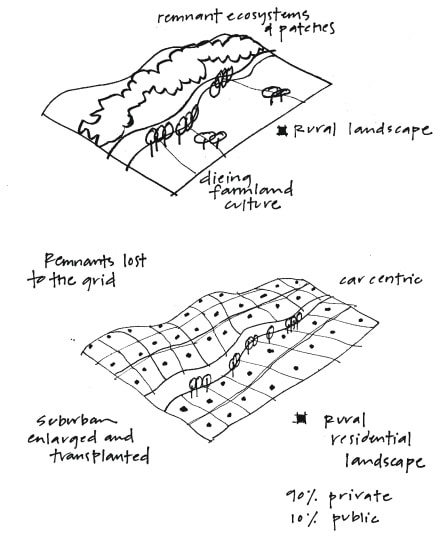

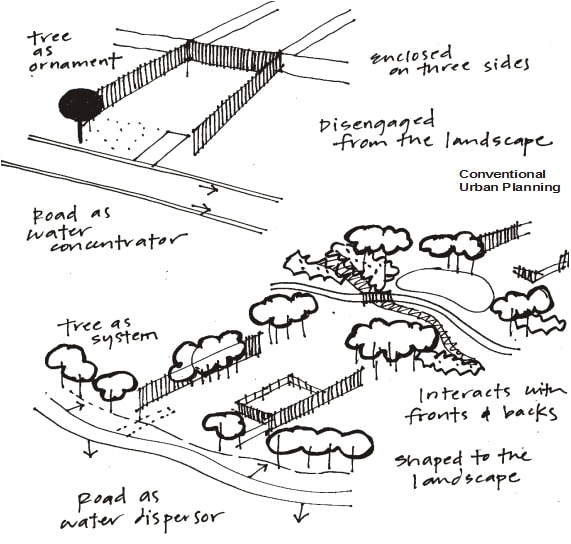

Spatial differences between conventional subdivision planning and ecovillage planning.

Social and environmental design factors differentiating layouts – Suburban Layout

Social and environmental design factors differentiating layouts – Ecovillage Layout

Elemental differences between Ecovillages and Conventional Urban Planning.

Ecovillages are sociable and varied in their spatial arrangement, and provide for community design and construction: their brief to be self-sustainable and non-impacting brings to focus a much higher level of design and infrastructure planning. The ecovillage is suited for use of marginal rural land, for sites with predominant biodiversity conservation values, and for growth in regional towns where options other than the suburban template would be a welcome character and lifestyle initiative. In Toogoom, Queensland for example, an ecovillage called Caral is being planned for 350 people utilizing defunct cane farms: it will create a solar array to generate communal power and the village will provide its own water supply. Such sustainable concepts are so far beyond Queensland’s planning mechanisms that new types of land use precincts are required to house them (John Mongard, 2004, p.1). The two following case studies show that this way of thinking and building can easily be accommodated within our current development and societal processes.

Ecovillage planning is premised on the notion that developing a community involves processes which need to move beyond setting out lots, into a collaborative ongoing process which involves residents in the design, making and management of where they live. This type of process currently only occurs in ‘fringe’ living places such as communes and alternative communities. The mainstream developer usually has no mode or desire for engagement with an emerging community once they have sold the land. The development of ecovillage’s such as those at Currumbin in the Gold Coast, and at Caral in Hervey Bay are attempting to engage with their emerging communities on an ongoing basis.

In moving away from the idea of inhabiting a suburb and toward that of being part of a community, people move the onus of responsibility and partnerships away from ‘others’ such as government and the market toward their emerging group (Kelly and Sewell 1996, p.106). Thus it is the partnerships formed by the residents that drive the vision and creation of urban forms such as ecovillages. The body corporate is a simple mainstream mechanism which allows these ecovillages to move outside of the conventional design and environmental standards for subdivisions, since the local authority is not directly responsible for the ongoing roads, parks and communities which are all managed and maintained through the body corporate. There is a clear demand for this type of lifestyle option as evidenced by the community consultation that John Mongard Landscape Architects have done in over thirty towns throughout Australia. This way of co-design with emerging residents is not some idealistic socialism, merely a practical process of building and designing with dwellers.

We should aim to achieve as much human habitat diversity as we find in animal habitats. Turner (1996, p.103-131) suggests that the traditional relationships between the constructive professions should be deconstructed in order to allow more variety of approaches and ideas, and subsequently create more variety of habitat and places. The idea of an ecovillage embodies diversity as a primary social and environmental generator. Figure 2 shows how the spatial layout of an ecovillage creates double active frontages, with the potential to facilitate social activity. This model has been successfully in place for over twenty years in the Village Homes development in Davis, California U.S.A. Central greenways, where clusters of homes can share a communal and productive landscape, are another spatial element in the Village Homes Project which encourages sociability (Figure 3). At Village Homes where sustainable community design was undertaken with the ecovillage principles outlined, studies showed that residents consumed half as much energy as those living in neighbouring standard suburban blocks, and that the crime rate was ninety percent less than those same adjacent suburbs. (www.lgc/freepub/land-use)

The ecovillage may be an emerging urban form to replace or supplement the suburb as a development template in many places where landscape and conservation values are primary considerations.

At a time when our towns are struggling not only against the big box, but also against the teller in the wall, the McDonalds in the service station and the Internet mail order, our urban and rural planning needs lateral problem solving. Many country towns and hinterland villages are ceasing to exist in this onslaught of economic rationalisation and privatisation of facilities and services. In the next ten years, many rural centres will retreat to the status of museums or tourism attractions. Can we assist in creating viable new urban and rural forms which retain their biodiversity and landscape centred-ness?

The rural hinterland morphing into a low density suburbia

(Case study: The Ecovillage at Currumbin, Queensland)

Southeast Queensland is rapidly morphing into a continuous fabric of suburban development. Interstate migration, sea change and the call of the sun are sustaining housing booms on the edges of Gold Coast City. The hinterland in Gold Coast City is subsequently loosing its rural character and landscapes. The developers of The Ecovillage at Currumbin in Gold Coast City set out to `build a project that inspires and sets a world’s best standard for the future community of Australia’ (John Mongard, 2003, p.1-2). The proposal is to develop an alternative approach to conventional rural residential development by using ecologically sustainable principles. With this notion came the challenge to prove to the local community that suburban sprawl was not just about to begin in their lush hinterland valley.

The brief was strongly influenced by the community design process enacted, with the visions, concerns and ideas of the valley’s residents actively harnessed through onsite brainstorming over a period of a week. Over four hundred people attended these brainstorms, which were run from an old dairy shed on the property. This process showed that co-design is as relevant on a greenfields site as in the middle of an urban area with an established population. Whilst this participatory model has been used since the 1960’s, Australian subdivision developers have to date failed to embrace it as a means of creating better places.

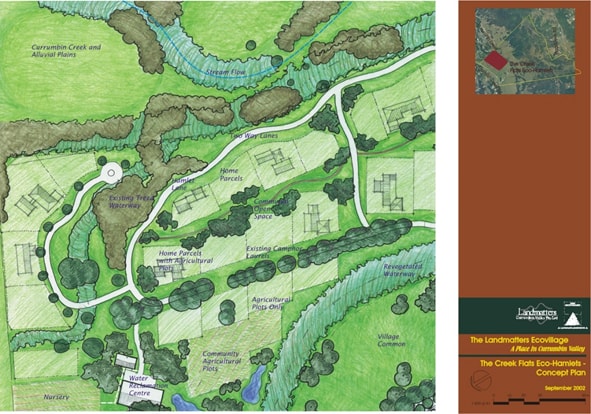

The subdivision process has remained unchallenged in the suburbs in the last thirty years. Landscape architects rarely get to draw up boundaries and parcels unencumbered by surveyors, or to create living places which are led by, not followed by, ecological development principles. The layout of an ecovillage strongly follows landcover and landform, creating eco-hamlet footprints which are created only on cleared lands. Figure 4 shows how the ecovillage at Currumbin not only retains the rural landscape but assists in ecological restoration. This is achieved by retaining 80 percent of the land as communal open space and developing cleared land for rural village living. The yield of the development is the same as that of blanket rural residential development, but the environmental and social benefits are much greater.

John Mongard Landscape Architects had some years earlier developed a city image strategy for the Gold Coast which included a community character study and design guidelines for Currumbin Valley (John Mongard et al, 2002, p.42). The crucial issue was how these beautiful hinterland areas could incorporate change and growth without loosing their rural qualities. In coming up with the Landscape Planning Strategy for the Ecovillage at Currumbin, John Mongard Landscape Architects walked the land with the client and team many times and together developed a shared-vision of how to sit gently on the land. The surveyor was called in to peg home parcels with a GPS system in the bushland slopes, once all the environmental analysis and sieve mapping had identified the best living places. Currently there is a waiting list of people for the 140 or so community title home parcels, indicating that the dream of an ecovillage is a tangible alternative for people seeking a more environmental future. The goal is to sell home parcels which are the equivalent cost to a traditional suburban or rural residential lot. If this is achieved, then the ecovillage will set a powerful precedent for an alternative model to suburban and rural residential development in the hinterland.

Urban / Suburban / Rural

There is a slowly rising call in Australia to build living places which are not `urban’ or `suburban’ in character, particularly in rural and hinterland areas. The suburban design standards which are now templates for all types of urban growth, whilst being effective and safe, are destroying the very qualities which people seek in rural and bushland areas. The Ecovillage at Currumbin has developed detailed environmental strategies and design codes which will hopefully lead to a change in approach and will give more than just lip service to environmental sustainability. The process as well as the outcome has to be a model for change, and it is the co-design model of participatory planning with the future dwellers at each stage of planning, design and construction which will create the pride and ownership the new place.

Currently, over fifty percent of our energy usage in the suburbs of South-East Queensland goes to heating water. The wastage of water and energy is a characteristic of the suburban model for development. The Ecovillage at Currumbin will address all aspects of energy use and conservation, from the use of local materials and technology, to the `closed-loop’ paradigm for keeping all materials and wastes on-site and recycled. For the landscape, this means that every material will have multiple roles and plants will be utilized to filter and absorb nutrients. All storm, roof and site water is re-used onsite for growing landscapes. An onsite recycling centre will separate glass, plastics, organics and even recyclable white goods.

The outcome of suburban sprawl is usually an immediate change in landscape character. The Ecovillage at Currumbin has sited each home parcel with the goal of achieving minimal visual impact on the neighbourhood. Revegetation and swales will be pre-grown and weeds will be progressively removed from the site, allowing new homes built into existing landform niches, to nestle around thousands of existing trees. Very little landworks will be required with the design; some lanes will be built out of concrete, allowing hillside soil profiles to remain untouched. Very little kerb and channelling will occur on site. The infrastructure is being re-invented and moved from conventional pipes and roads to soft and environmental infrastructure solutions.

Part of the ongoing decline of our rural areas is the loss of small lot food production. Is it possible to grow food near where you live, even if you are in the

Concept Plan for a typical Ecohamlet at the Ecovillage, Currumbin, showing dual frontage home parcels with central and perimeter food gardens.

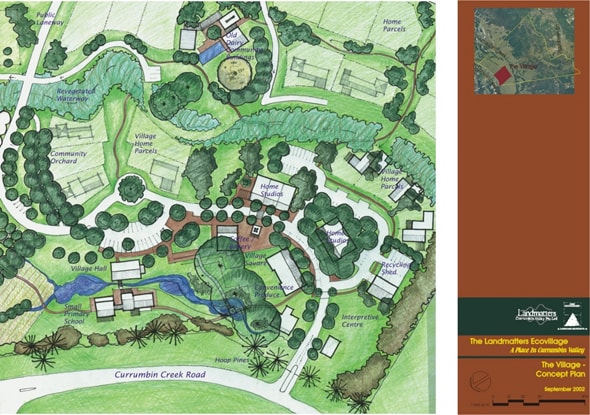

Concept Plan for the Village Centre at The Ecovillage, Currumbin, showing work/play/live nexus created around a food-cooperative shop to sell village produce and home studio/small lot living nearby.

suburbs? Breaking the division of living places and food production is one of the urgent agendas for creating a sustainable future. At The Ecovillage in Currumbin, all scales of food-productive landscapes will be implemented, from community orchards through to private and communal vegetable patches. On site waste treatment will create irrigation water. A food co-op will sell the produce in the village centre.

Moving away from the unsustainable cycle of suburban sprawl requires fortitude and leadership. The ecovillage in its contemporary urban form must create a new benchmark for the `subdivision’ process. If it survives all the economic and planning pressures, the ecovillage model could become a new template for living within our ecological limits.

The Village about to be swallowed by suburbia

(Case study: Tooradin Village Strategy, Casey City, Victoria)

There is a gateway to the sea

one place

in Casey City

where the artery of the region

touches the water

on its way to the penguins..

A window to the world

but the curtains are slightly drawn

hiding natural things

which hold the promise of visitation

for the City.

It has salt marshes

of national repute

a tidal ecosystem of value

lush pastures

and growing land and soil

in this place

where nature

retains its integrity

Can the City

protect and nourish it?

If this nature

holds the key to its attraction

then it follows

that nature should lead the planning

The bringing back

of an intact environment

from a distant past

is beyond the Council.

But it may not be beyond the villagers

For each successive action

of building or change,

Tooradin’s people can heal

the village.

Trading economic value with

environmental re-connection,

an idea about credits emerges:

if you give the village

a green belt

you will gain the right to

more living space

if you give us a public space

or a walkway

we will trade with car park

reductions.

No one has lost anything

but there is much

to be gained

by all.

The promise of better things

must surely lie

in any strategy for the future.

Village / Suburb

Tooradin is strategically located at the only place where the South Gippsland Highway meets the waters of Western Port. The Village is located 65 kilometres south east of central Melbourne. The tremendous population growth potential of Melbourne’s south eastern corridor (an emerging urban conurbation) provides opportunities for Tooradin to perform a unique role as a place for living which retains it rural and environmental assets and resists being engulfed by Casey City’s suburban growth. The Tooradin Village focuses on a combination of urban design, planning and economic cost-sharing mechanisms to achieve biodiversity conservation and to promote a sustainable rural village lifestyle.

The Tooradin Village Strategy aims to be a model for the whole of Casey City; serving as a valuable precedent for maintaining the rural village as a viable urban typology against the onslaught of suburban sprawl. The re-positioning of the village’s future has emerged in response to the involvement and visioning of the local community who actively helped to shape the Strategy.

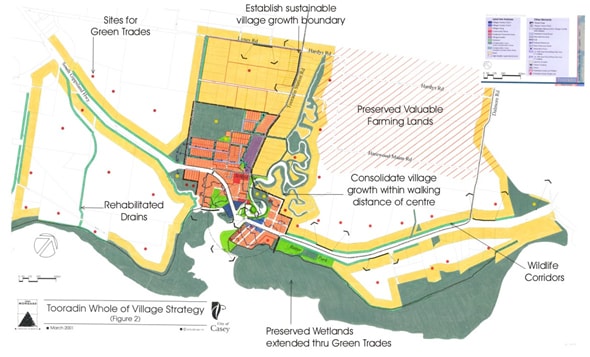

Traditionally, Tooradin’s development has pushed out indiscriminately into the surrounding rural landscape. As a result, local ecologies have been compromised and natural systems disrupted. The Strategy reverses this past development – model and aims to actively rehabilitate the local ecology and promote sustainable development. The design philosophy is one of the local environment filtering through into Tooradin Village, instead of the Village pushing out endlessly. For example, the Strategy proposes a series of new linked wildlife corridors within the Village to help bring back Tooradin’s natural qualities.

Tooradin in 2000 was on the verge of a new wave of development pressure. The catalyst for this change was the imminent connection of the village to reticulated sewerage, which will eventually triple its population. The Strategy provides direction as to how new and ‘greenfields’ housing growth can be best managed within a rural village setting. The plan allows for the following key outcomes:

- Each vacant and infill lot to be assessed for its ecological footprint,

- Consolidation of lots and further density within walking distance of the centre as a trade off to limiting rural residential development on the periphery,

- Turning the village’s most important hill into a conservation reserve through a green trade,

- Establishing a population limit and growth boundaries for the village based on ecological carrying capacity.

- Identifying land and corridor for environmental purchase, healing and conservation through green trades. Eg allowing additional houses in predetermined rural land in exchange say for valuable wetlands or wildlife corridors.

The Green Trades

To create the desired future for Tooradin’s natural environment, a system of Green Credits has been implemented: a system of economic incentives to act as a catalyst to bring about significant positive environmental change. The local council trades the rights for additional development with that of significant restoration of the natural environment. This is termed a Green Trade. The starting point for all Green Trades is that the environment is the primary beneficiary; additional development is a negotiated by-product, and is in no way to drive the decision-making (John Mongard et al 2001, p.10).

Tooradin Village Strategy showing sites for Green Trades.

Tooradin Village Centre Strategy, showing community-led initiatives which are currently being implemented through a participatory planning process.

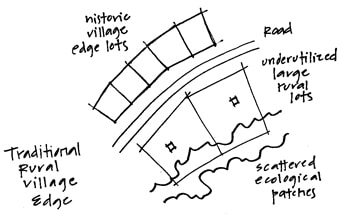

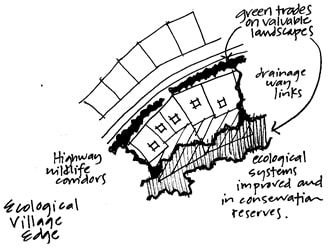

A Traditional rural village edge

A transformed rural edge using green trades to achieve ecological landscapes

A Green Trade is considered by Council where there is a clear net community and environmental benefit and Green Credits are not limited to a particular property. This means that, a landowner in one part of Tooradin could re-vegetate a property, or hand-over to the crown valuable wetlands or turn a drainage channel into a wildlife corridor, in exchange for additional development rights in another predetermined location (refer Figure 9). The principle of a green trade is that fifty percent of the value created above the original sale price of a newly created green trade development property goes to the landowner and fifty percent goes back into Tooradin’s environment. The process has now been actively working for two and a half years and has been well embraced by the local community.

The green trades system has yielded five conservation reserves to date, and has already added hundreds of hectares of valuable environmental areas to the pool of the common landscape. This has been achieved smoothly and at little cost to the local council. The idea of Green Trades has the potential to revolutionize the planning process for promoting rural character and biodiversity conservation in Australia, and is one of the first known process in Australia to be implemented in such a proactive community-led way.

Inside Tooradin

Tooradin has a special village quality and character. A village is a compact and walkable built area where residents have a strong sense of community and place. The Tooradin community does not want the ‘village’ character changed by insensitive suburban and retail development. But how can you find this collective village character or sense of place? Where is it? It hides and then becomes revealed when one experiences a place and its people deeply. This is an important philosophical practise for working toward intentional community and picks up on fundamental ideas about ‘being’ and ‘place’: that only if we are capable of dwelling can we then build (Heidegger, 1975, p.160-161). The designer must become like a dweller to build well in a particular place. At Tooradin, the design and planning team worked from the Village hall for four weeks of intensive co-design with the community. This process extended over a period of one year, allowing for a reflective and participatory model of deciding priorities, works and community visions.

The Village Trades

The Tooradin Strategy also provides for village trades, which are economic/ planning mechanisms in action to promote village character and create urban design incentives within the centre. The village’s main private landowner and developer has entered into a collaborative design process. The development of a “big box” has been shaped as part of the process, consolidating the main street with an appropriately integrated supermarket, restaurant, shops and motel. This iterative place making process ensures that Tooradin’s economic heart will not be split up.

The community’s dream of linking the two sides of the village split by water and highway is being realized through a co-design process to create the creation of a village promenade and landing for boats. These plans are currently under development for construction in 2004. The Village Pub will be renovated to face the new harbour landing and the owners of the pub will contribute ten percent to these works and move their car park and drive-through to achieve a better village outcome. The adjacent Village Sports Reserve Complex has been reshaped in collaboration with six sporting clubs to allow for creation of a lawn bowls club to cater for the ageing population. Land will be purchased shortly for consolidation through a village trade with the sporting club, thus minimizing the improvement costs to the Council to fifty percent.

The process being undertaken in Tooradin is holistic, comprehensive and culturally embedded. Strategic planning moves into design and construction through a long-term process which involves the community at each step. This type of place making accepts that cultural and community planning is a network and a process, not a series of isolated events, constructions or projects. This model has much to offer for promoting a viable placemaking theory in the practise of landscape architecture: it calls for social and environmental planning to be inexorably woven through an interactive practice.

Conclusion

If our profession is to emerge as more than one of window-dressing, then we need to be bold enough to help find solutions to the difficult problems facing our communal living places. How do we actually create places of social and ecological diversity? What are we to do with the bored teenagers that wander around our outer suburbs looking for a place to go to? What kind of places will sustain us when we are all old together? When we are too old to drive to the big box or too far away to walk to the centre? How sustainable will the suburbs be when the price of crude oil triples?

Both rural and urban growth areas need to proactively tackle the retention of landscape values and the ongoing clearing of bushland. As Yencken et al (2000, p.210) point out, strengthening biodiversity conservation requires strong strategic frameworks which need to tackle not only protection of land but also the ongoing progressive restoration of degraded landscapes. The Tooradin Village Strategy aims through its multi-pronged approach to bring biodiversity into a central place in the planning for growing rural communities. This is currently not common practice and needs to become so.

Ecovillages such as Caral and the Landmatters Ecovillage at Currumbin are trying to promote a more sociable and environmental type of living place. This requires stepping out beyond the subdivision and infrastructure standards and the invention of new ways of building houses and landscapes. Such new templates and pattern-languages are urgently needed to help the australian construction and development industries become sustainable, but more importantly to give Australians better choices for how and where they can live in more environmental ways. Bainbridge (www.ecocomposite.org) clearly outlines how the Village Homes sustainable community in the USA has been able to successfully implement such ideas since 1974.

We can help local people identify their unique environmental and cultural assets and assist in letting them invent a relevant future for themselves. We can build what Freire (1993, p. 107) called a process of reflective action, which in this scenario incorporates developers, designers and future dwellers in an iterative community building process. This would nurture the type of participatory economics which Albert (2003, p.143) calls for as a basis for living in the twenty-first century.

We can listen and learn from these local dwellers and develop new pattern languages which are culturally embedded and tied to local landscapes. This customisation of communities is a means by which Ellyard (2001, p.174-185) believes we can achieve prosperity and sustainability.

The idea of a local place with a strong community is still the most potent agent resisting the changes wrought by globalisation culture. Local places. Local people. Local landscapes of significance. Local work. Local play. Local food. Local materials. By assisting the local, we can play a meaningful role in the making and remaking of our places.

We have talked much about the suburbs and the subdivision ‘product’ since the 1970’s but we are yet to reach a critical recognition of the causality which prevents true sustainability as new and existing places grow. We have to try new ways, because ‘it is the constant building of a thinking in which to dwell, and upon which dwelling depends’ (Fry, 1999, p. 289) that will move us toward a more sustaining placemaking.

Despite all the technological innovations in our lives, it remains true that people like to be with each other and have a need for community life and activity which is free and spontaneous. Striving for a meaningful process of building sustainable and sociable communities is a practise worthy of the future.

References

Albert, M. (2003). Parecon – life after capitalism (Participatory economics). London: Verso.

Bainbridge, D. Sustainable Community – Village Homes. California: Davis

www.ecocomposite.org/building/villagehomes.htm

Ellyard, P. (2001). Ideas for the new millennium. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Freire, P. (1993). The pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Penguin.

Fry, T. (1999). A new Design Philosophy and Introduction to Defuturing. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Heidegger, M. (1975). Poetry, Language, Thought! USA: Harper & Row.

John Mongard Landscape Architects. (2003). The Landmatters Ecovillage – A Place in Currumbin Valley. Concept Plan and Landscape Planning Report. Brisbane.

John Mongard Landscape Architects and Casey City Council. (2001). The Tooradin Village Strategy. Brisbane.

John Mongard Landscape Architects and The Urban Design, Cultural Heritage and Landscape Unit. (2000). Landscape Character: Guiding the image of the City, Gold Coast City Council. Nerang.

John Mongard Landscape Architects. (2004). Caral Ecovillage @ Toogoom – Design Strategy Report. Brisbane.

Kelly, A. and Sewell, S. (1996). With Head, Heart and Hand: Dimensions of community building. Brisbane: Boolarong Press.

Local Government Commission. Toward a better Neighbourhood Design.

www.lgc.org/freepub/land-use/articles/energy-betterdsgn-cont.html#success

Turner, T. (1996). City as Landscape: a post-postmodern view of design and planning. London: E & FN Spon. Yencken, B. and Wilkinson, D. (2000). Resetting the compass Australia’s Journey towards sustainability. Victoria: CSIRO Publishing.