The public realm is a complex place: a slippery cultural construct. It is shaped over time by many intentions, mostly non-design related. How can landscape architects become meaningful players in this shaping process? How can our public spaces become cultural realms?

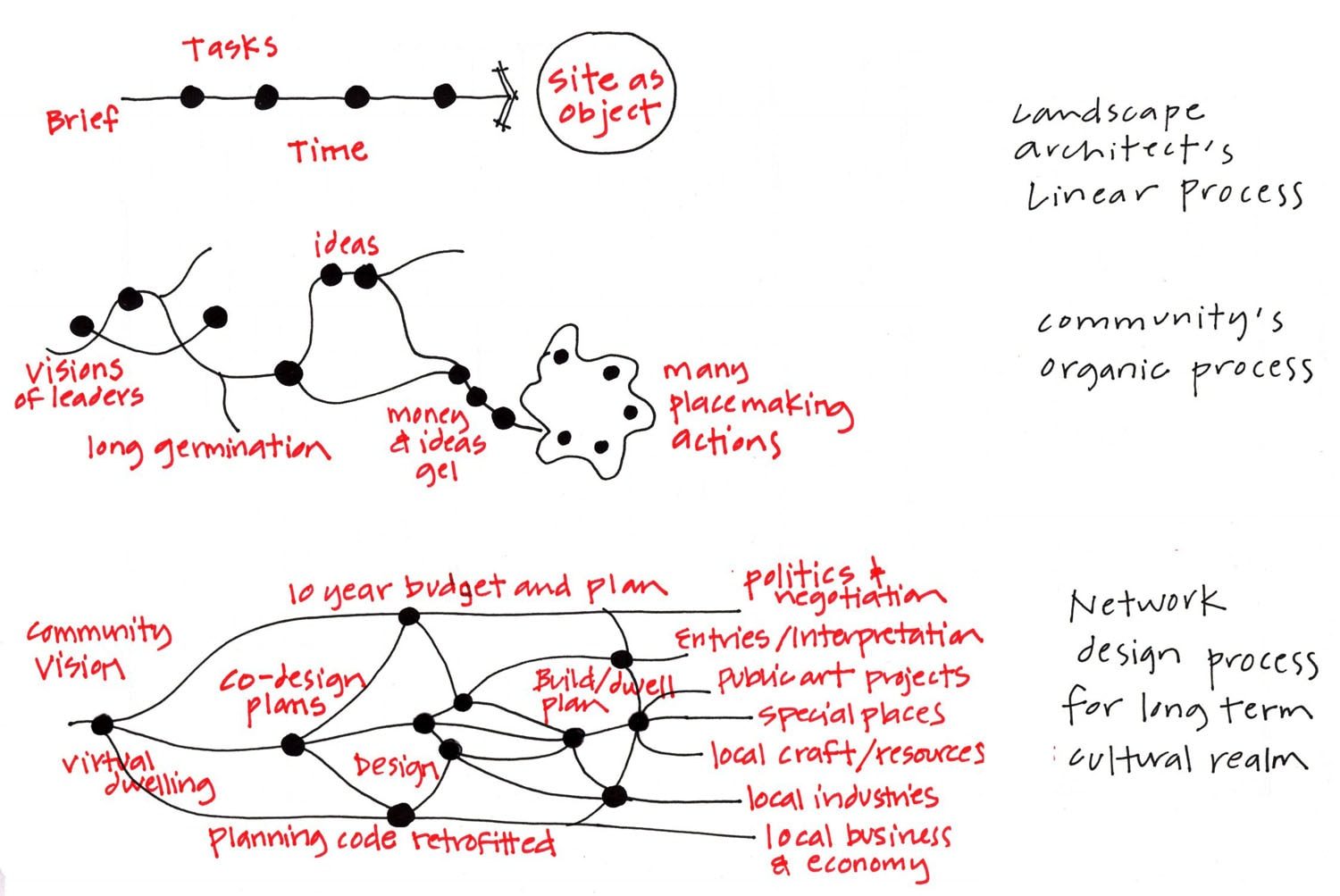

‘Projects’ are design and construction vehicles used to solve perceived public realm problems. They have very specific time, budgets and players: clear, linear processes.

‘Public realm’ by its nature has no specific time or site: it constantly changes around people, buildings and the landscape. Its culture is layered over time by a range of insiders and outsiders to the place, most of whom have never heard of a landscape architect and who perceive their places in an organic and non-linear way.

Landscape architecture has inherited from architecture a design process geared to ‘projects’, not to ‘public realm’. Our processes need to be sophisticated enough to deal with the reality of places which have political, social and environmental conflicts which move in time and space, often making the ‘site’ and the short-term ‘project’ figments of our professional imaginations.

Geographers, social planners and community development theorists have been writing about such public realm shaping issues for some time (Ellyard; 2001, Sandercock, 2003). Until we develop more complex social theories and cultural processes which we can implement in the ‘landscape architectural project’, we may continue to be accused of window dressing.

A more time and culturally layered process is required which creates a network of projects without edges and which allows people active participation from visioning a future, to caring for an outcome: a network design process. This requires the re-invention of the time/site structure in our work, and a re-definition of the landscape architect; not just as designer, but as concurrent mediator, urban manager, collaborator and educator. Case studies of processes which have aimed to network and build many ‘projects’ into a public realm over periods of five to ten years will be offered as starting points. Built placemaking projects in an Australian city, three regional towns and in a smaller centre will be used as visual examples of the approaches being discussed.

The Landscape Architectural Project

The landscape architectural project in practice is defined by the sequential design stages and services of a consultant’s task and fee schedule, and is focused on the site.

The intent of a project covers many pragmatic as well as visionary goals; for the landscape architect, this straddles such divergent things such as making money and helping to create better places.

Environmental and cultural concerns are usually not specifically defined in fee schedules, but are implied by the brief or sometimes projected by the values of the designer. Environmental concerns are easier for landscape architects to address since decisions about plants and materials are directly related to the implementation of the project. Cultural concerns are not often well defined and require a level of translation which affects the process as well as the content of the landscape architectural project.

A collaborative process where designers, developers and dwellers envisage and build together is rarely a linear process.

Most of our suburbs have impoverished or privatised public realms.

The direct and linear nature of the traditional landscape architectural project appears to move us neatly through concept, design development, documentation and construction administration. The making of a public realm however is never neat or linear and involves a multilayered process requiring a network of actions and visions.

There is thus a large gap between our contemporary projects, with their linear steps and programmes, and the organic way in which places are made ‘outside’ of the project and in the real world.

Changing Paradigms

We should spend more time worrying about the networks and less time on the lines in the landscape architectural project. Whilst pattern making is one of the important artistic dimensions of our work, it does not lead to the making of place. Modernism has encouraged a superficiality in our plans – a kind of dumbing down of places to a palette of easily repeatable colours and gestures, reinforced by computer aided duplication.

The conventional consultant fee structure and current neo-rational economics collude with this uni-dimensional design process to create a paradigm for an impoverished public realm. We deliver what the market wants – fast landscapes at expedient prices and with an impassive cultural dimension, if any. Even local authorities are now run like businesses, moving their core away from public goods toward the lowest common denominators in place making. Less is not more in public space. Open space (parkland) is failing to merge into urban spaces, which are gravitating to become closed space: privatised, leased or rented public territory for consumer related activities.

Outside of this commercialised landscape are the ‘special’ projects – large public areas designed to make up for our anaemic suburban fabric. Waterfronts, urban village centres, botanical gardens and regional parks and event spaces are examples of special projects. These projects are mostly run through conventional landscape architectural processes and deliver gentrification faced with overpriced beauty. They gobble up all the resources and funds for public realm and are often not able to interact with their communities and local cultures for fear of missing political deadlines, slowing the process down or ruining the designers’ aesthetic.

There is fear that networking large projects into their social and communal fabrics will open them up to critique and to the interactions which ironically would best integrate the project into the place fabric. We are left with jewels sprinkled in mud. The suburbs, the local parks, the rural periphery and the places where ordinary people live: all left to non-design or less design. These are the ‘other’ landscapes predominantly not in the awards and publications. Landscape architecture is possibly the best profession to help knit a great public and cultural realm in the other landscapes as well as in the heart, but it cannot do this with conventional processes and a culturally bereft paradigm. The great places of the world succeed in making the ordinary special, which is a much harder task than the creation of a few special places set amongst the ordinary.

A Better Model For Placemaking

Local communities have grounded and experiential knowledge about their places which don’t manifest themselves in conventional design and planning processes. Their stories and other ways of knowing are storehouses of place wisdom. (Sandercock, 2003 pp.210). The old process of drawing a plan, presenting it for comment and then building the works is clearly an inadequate model for placemaking in our times. We need interactive processes that involve the dweller/user/community in each stage of the placemaking process. This requires a change in the structure and content of the planning and design process. By crafting place and story insitu with local people and local artisans, we stand a chance of creating local meaning in place.

The local crafting of place creates meaningful material quality.

The Island Beautiful Plan for Mabuiag, Torres Strait.

Years of further habitation lead to the layering of place which we as designers so desire. These processes do not happen quickly: there is inertia in our cultural and economic patterns. We are mostly at the mercy of one-off projects with short-term budgets and time frames and it is up to us to invent a better process for our clients and for our places.

Landscape Architects need to tackle the social: to find a middle ground between the individual and the communal, with the accommodation of the poorest and least able dwellers being the litmus test. The social and the cultural are the hard to grasp intangibles that sit behind our ‘sites’ and ‘public spaces’. Without a strong cultural dimension to our projects, they will never be more than greenery placed on architecture.

Is landscape architecture an important contributor to making places or is it an optional add-on? We recently did work for a remote community in the Torres Strait, a fishing island called Mabuiag. The island’s residents have little means to support themselves and are strongly reliant on government. Faced with a lack of water, housing and poor health, Mabuiag has fundamental development issues, and yet the key outcome of consultation regarding their future yielded a vision to create a better village centre. Their ‘Island Beautiful’ vision seeks to reinforce the social and cultural through the landscape, despite and perhaps because of other deeper seated community issues which will take a long time to resolve. Landscape architecture must provide cultural as well as environmental solutions in even the smallest communities because people always have a need to dwell together.

Past and Present Examples

Traditional vernacular villages offer us examples of a time-layered way of placemaking within a local culture. Italian medieval villages are a good example of high quality places built by a close networking of local communities, designers, builders and resources. In such places, great building made settings for the city to grow into and strong cultural values and habits amongst their communities led to high quality and well-used public realms.

Designers and groups who have attempted substantial long-term networks of public space improvements include Andreo Palladio in Vincenza, Italy, during the Renaissance; Baron Haussman in Napoleon’s Paris, and Barcelona City Council at the time of their hosting of the 1992 Olympics. Such examples have often achieved their outcomes through fairly autocratic processes where the public realm was perhaps a biproduct

and not the focus of these urban interventions. (Expressions of worth, security or image being predominant motivators).

Buildings and space seamlessly create public realm in Sienna, Italy.

Innisfail’s urban renewal occurred over a five year period involving hundreds of people.

Community designing for the community in a co-design workshop.

Can contemporary landscape architecture achieve a networked public realm of high quality and through democratic means? In our regional placemaking projects in Atherton, Kingaroy, Stanthorpe and Johnstone Shire in Queensland, John Mongard landscape Architects (JMLA) have begun with whole of town strategies and then assisted these communities in implementing a network of large and small projects over periods of five to ten years. Such design/planning relationships allow for long-term placemaking with focused cultural goals. Our work in five towns and their surrounding regions will be used as examples to highlight directions raised in this paper: Atherton, Kingaroy and Stanthorpe are medium sized regional agricultural centres, whilst Innisfail and Gladstone are emerging larger regional hubs or cities. These places have been undergoing renewal of their public realms through a network design process, and I will use them as examples to discuss the following design directions.

Networks Not Lines

Landscape Architectural practice and design process owes much of its structure to architecture. The architectural project is strongly focused on the building/object/site confluence. The landscape architectural project however always spills out into its context: searching for connections, aiming to bind sites into the broader city / region / landscape. As such our methodology requires a network of actions and activities, not a singular timeline focused on one object of design. This network approach has many implications:

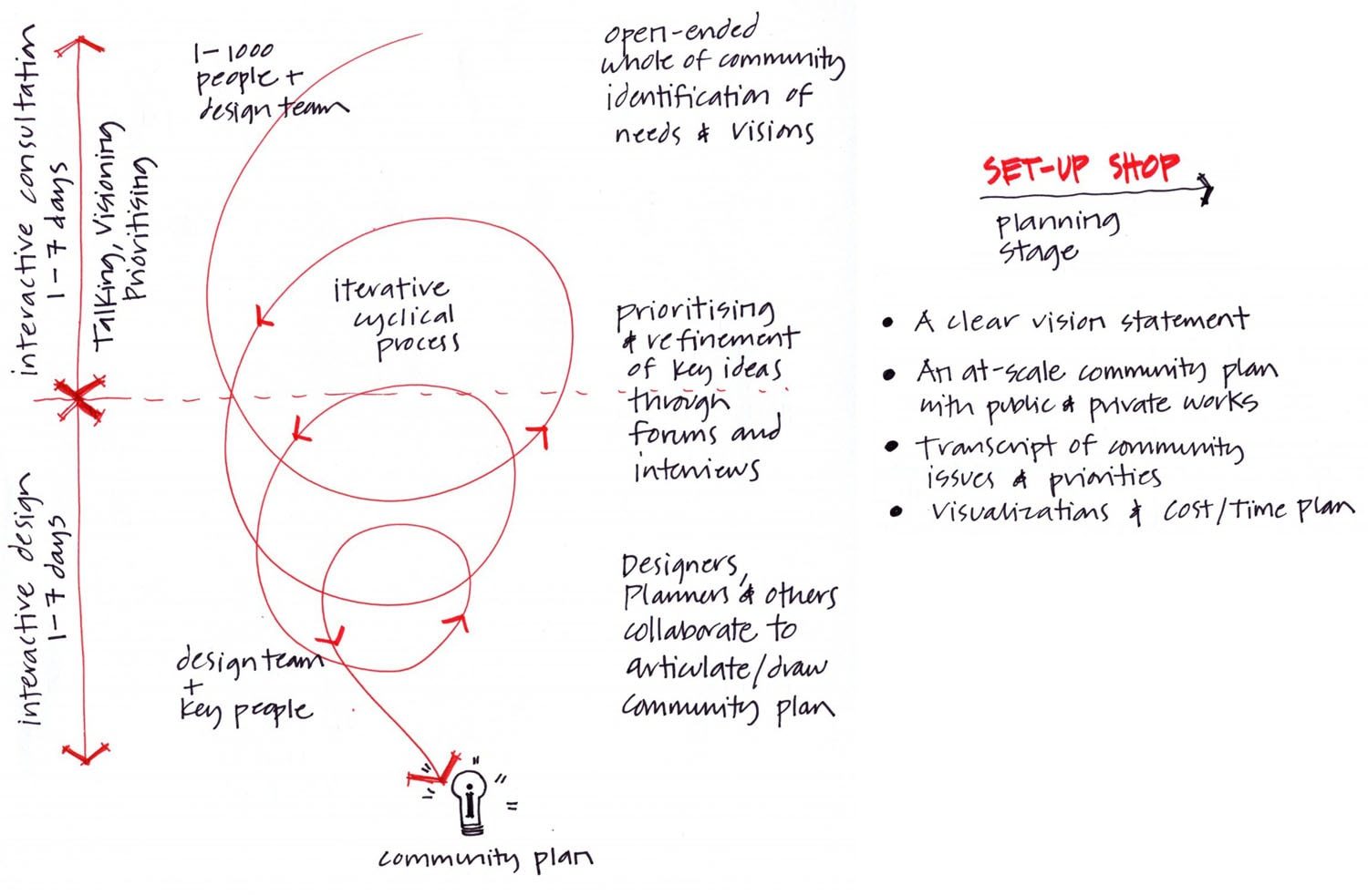

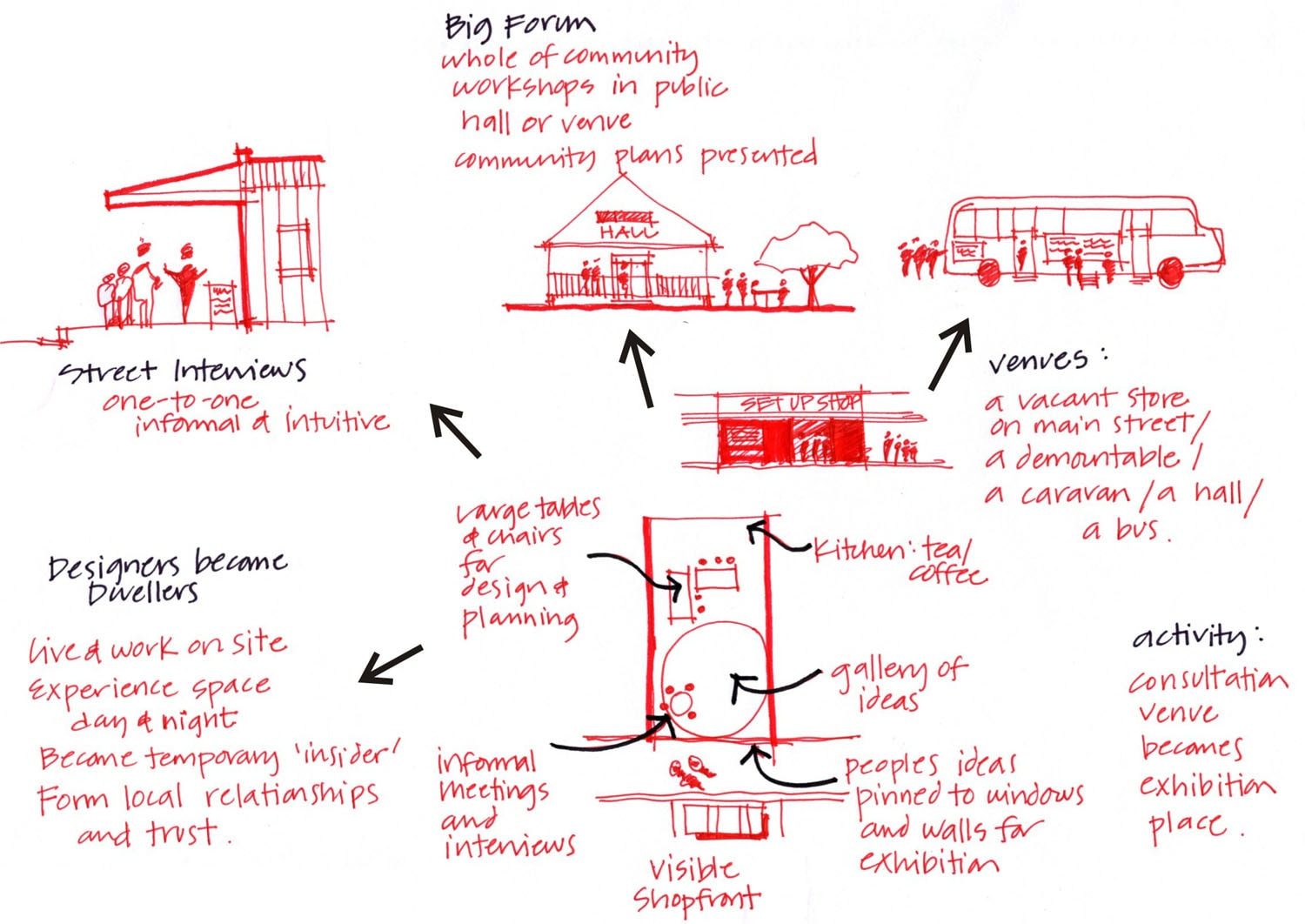

- Networking requires co-design: the talking and designing of places into being with communities rather than the isolated consultant in the office model, is a better process for public realm solutions. Much more time and resources are directed to co-design in a network design process: the goal is to ‘build in’ local values, culture and landscape as the designs emerge.

- The landscape architect when insitu acts as a mediator between conflicting community issues which can often only be solved through talking. This mediation is often the most critical role in the success of implementing a public realm.

- Without constant mediation, important projects are without a political/cultural edge and flounder on local conflicts.

- Collaboration – we invariably spill over into other ‘territories’, needing to, for example, change engineering infrastructures to make an environmental outcome. Engineers with environmental training and values are thus emerging as one of our most valuable collaborators in implementing the sustainable landscape. New infrastructures are emerging which are mainly the outcome of network thinking.

- Design process needs to modify to create a network of concurrent design and planning actions. At each step the network is iterative by virtue of its co-design (designing with community) processes. (refer to following diagrams).

Linear, evolving and network design processes

Co-design process (designing with community)

Design insitu: ideation, talking and conflict resolution. (The designer becomes a virtual dweller)

The city is a process not just an object

It is plainly just not enough to build well and to solve the pragmatic problems. Designers need to tackle the sublime: the experiential and the emotional needs of dwellers. These are the unlocking boxes where we find those finer layers that allow people ‘to dwell’ and make place. Our design methods could consider the following:

- The site within its place and region can only be well understood when the designer has an ‘insiders’ perception. The concept of the designer becoming a ‘virtual dweller’ – someone living in the place and experiencing it at all times and in a shared way with other dwellers, forces a change in the structure of the design process. Design and analysis occur insitu and in an interactive, circular way. Good design solutions flow easily in this close place/designer/dweller network.

- The collaborative design processes necessary to achieve great place making are similar at differing scales and city densities: to create real community, people need to actively participate at each stage of the process. Residents can invent and dream at each stage of the place making process, irrespective of the size of the place.

- Traders, owners and stakeholders become active collaborators: public place can be successfully activated by the interactions and involvement of adjacent business. Joint funding and dreaming occurs in great public space projects, straddling both local economics and visioning.

In the country town of Stanthorpe residents dreamed and then built a piazza for their special events.

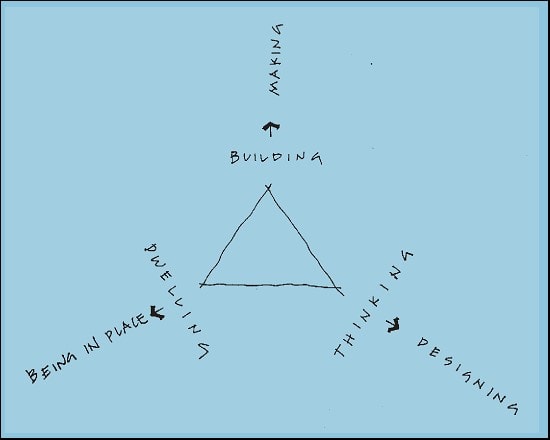

The notion of ‘dwelling’ underpins the design and building of places in a culturally oriented change process.

Changing the Content of Public Placemaking Projects

The landscape architectural project needs to consciously push the envelope of environmentalism and social equity if it is to have any hope of creating a long-term public realm. The short-term culture of consumerism, pushed by rational policies and globalisation, is a dominant paradigm spilling out from the private to the public: it would have us create disposable short-term landscapes suited to the needs of only those who can afford them. Material quality in this context is a symbol of gentrification rather than a desire for great public space. The following design content directions may assist in shifting the focus toward a more sustainable public realm.

The Innisfail Revitalisation Plan in tropical Queensland was implemented exclusively using local industries, art and crafts.

The Hou Wong Chinese Temple and Interpretive Museum, Queensland: Part of ten years of cultural planning in Atherton Shire.

Local Networks build Sustainable Places:

- Landscape resources and products which are locally sourced, owned and made will support local culture and economies.

- Projects can be broken down into a network of smaller making events, allowing the skilling up of small local constructors, artisans and suppliers. This fosters emergent local industries.

- Specify materials and products which you know will minimise global environmental damage – high quality, low embodied energy and long lasting.

- Build for the long-term to avoid the consumerisation and unnecessary short-term visioning of public landscapes. Public realms should be budgeted to last for at least 50 years.

The Regional Landscape straddles the Global and the Local:

- Knowledge about the region when applied to the site creates the most realistic context of environmental and cultural indicators for a public realm. Regionalism allows us to address issues of globalisation and macro technologies, as well as issues of local character and local resources.

- Places with important public realms usually have a regional draw and so the ‘community’ on the edges is as relevant as the people in the centre.

- Establishing long-term relationships between designers and regions creates a context for a cultural realm, since ‘projects’ and ‘sites’ can be networked into a broader regional landscape with values and content which reinforce local culture.

- As a regional landscape programme evolves out of landscape projects, so the local industries and fabricators learn the skills to enable this landscape to emerge. This is how culturally imbued public realm is merged into local industry and economy.

Culture needs expression and place to be freely enacted in the City:

- Accommodation of the least able and least well-off in the community is the best social test of our public realms. Fight for the provision of public amenities in privatised public realms such as shopping centres and residential complexes.

- Event spaces of formal and informal nature, and of varied sizes, are crucial to provide a setting for cultural life to be fostered.

- The creative people in the city need to shape the material quality of the public realm through art, craft and design. In this way, the city takes on local meaning and identities.

Places require ‘networks’ not just ‘sites’:

- The public paths of the city must provide a connected experience worth walking, attracting all the senses and engaging the visitor. Sites need to be placed into a context of public access and walkways.

- Barriers to public access and movement need to be removed, allowing people to take precedence over cars, and to reclaim public space for gathering. Minimise kerb and channel in public realms and provide for the least abled as a priority.

- Anchor points in the journey (main destinations and event spaces) need to be housed in quality spaces which will last many generations.

- The signs, symbols and stories are focused on people and not traffic: a process of telling the city’s stories and poetry will enliven the journey².

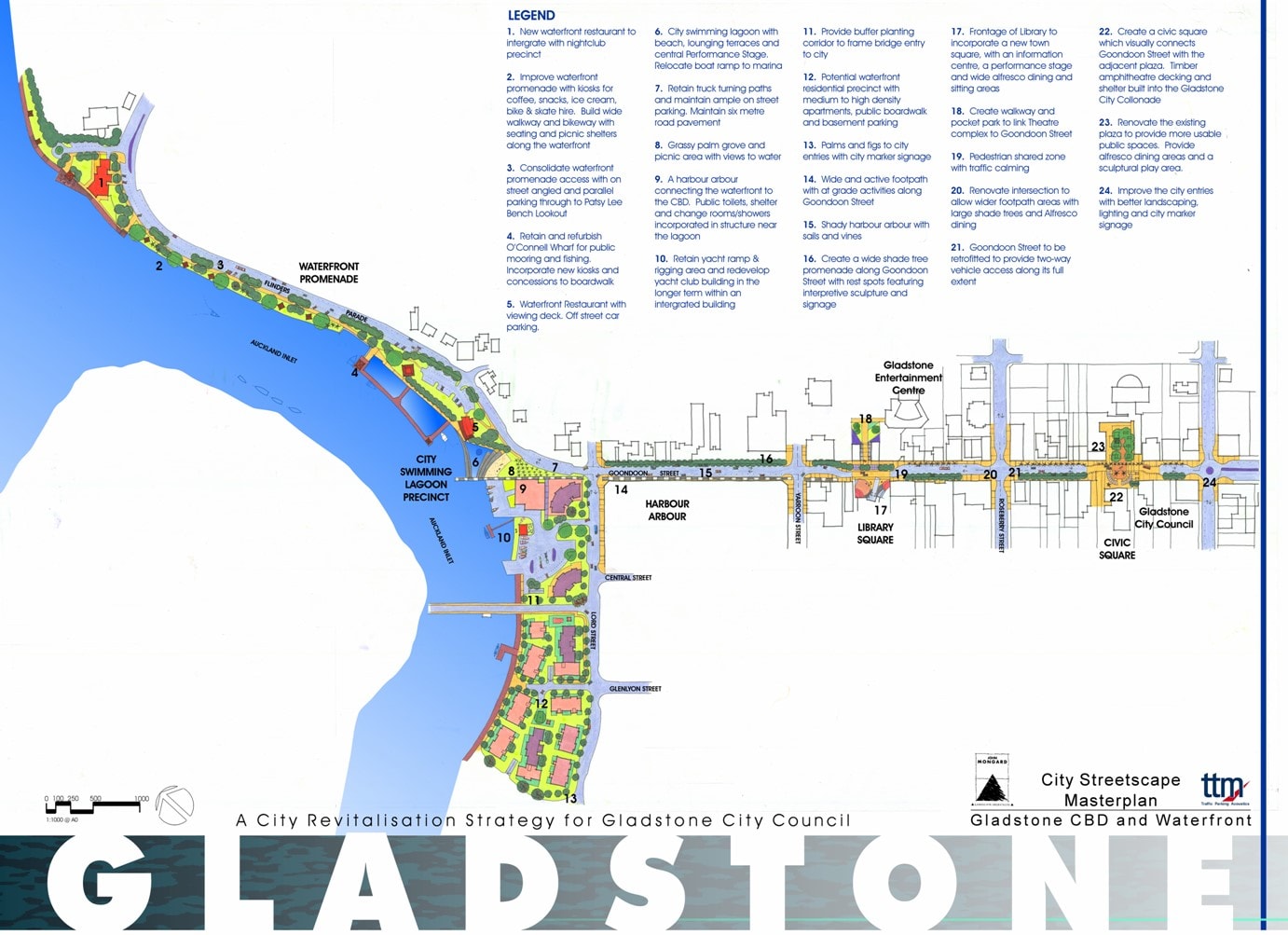

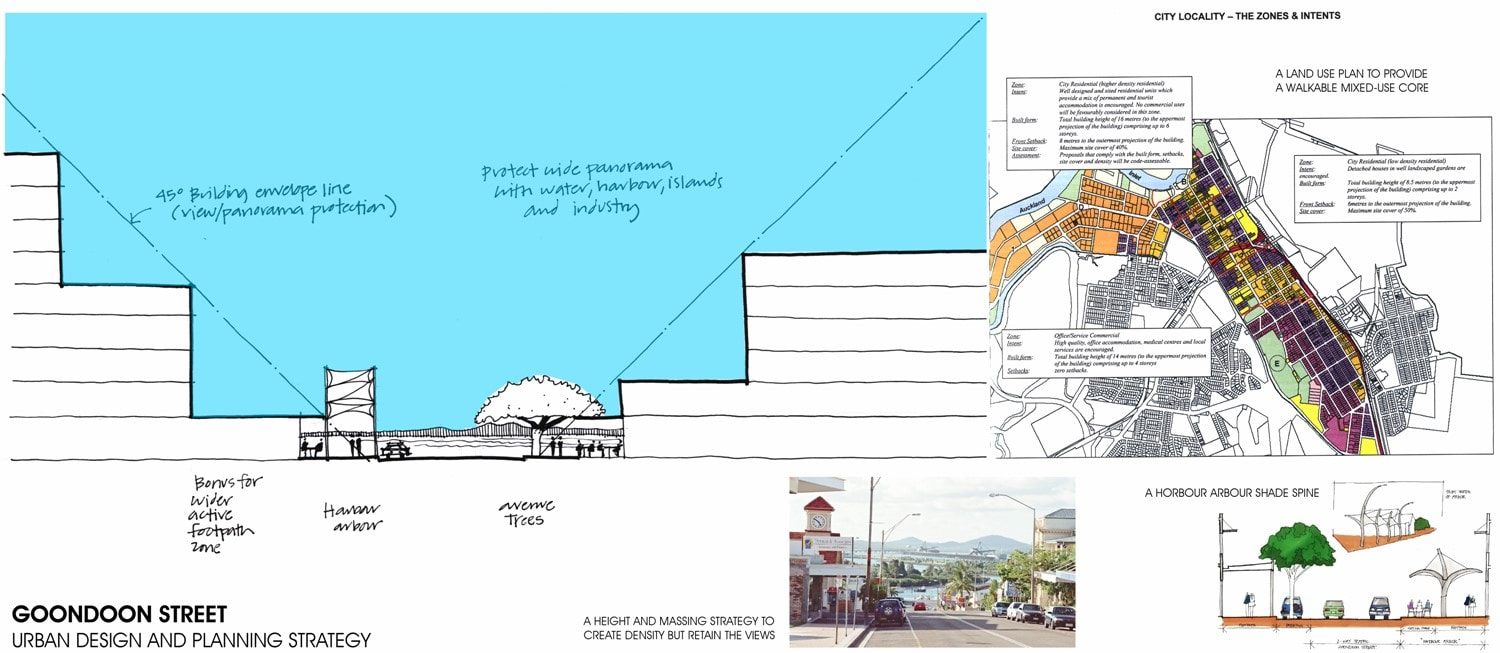

Strategic Planning marries town planning with public realm planning in the Gladstone City Strategy.

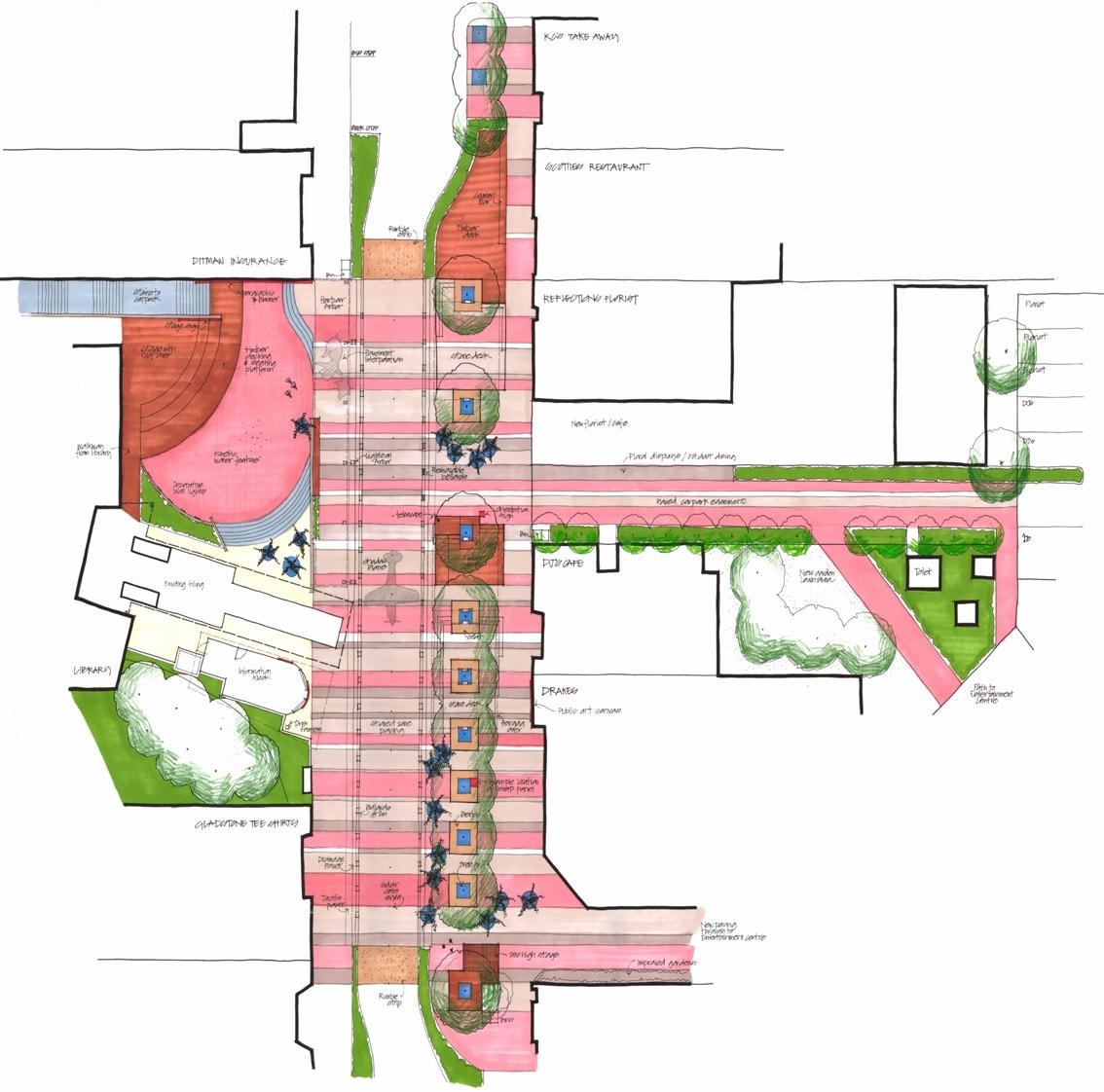

Library Square, Gladstone City: A public space to activate the city and its cultural realm.

Elevation of activated event at Library Square, Gladstone.

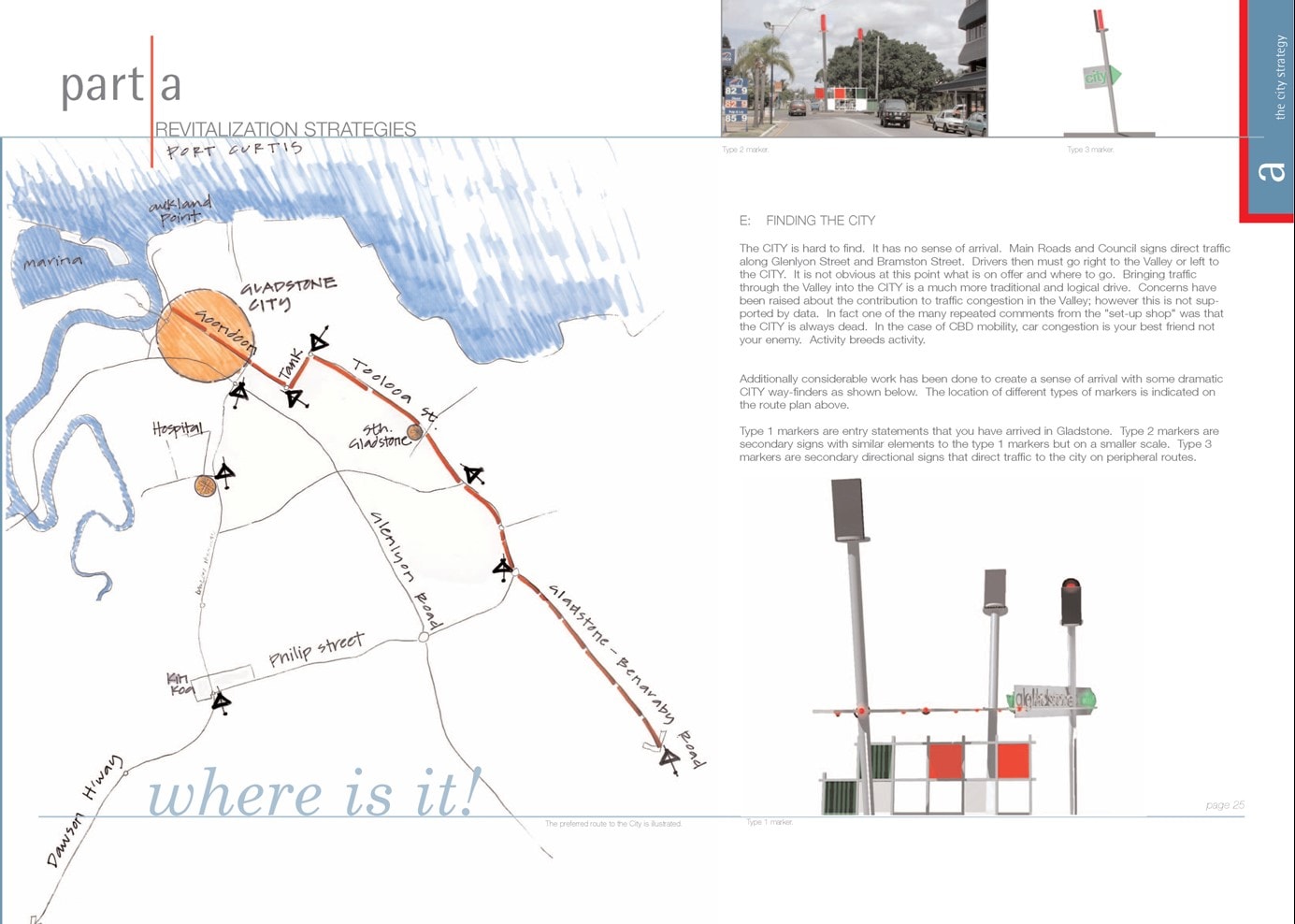

The Gladstone City Revitalisation Strategy is an example of a network design oriented process. Community design and visioning established the key elements of the strategy, and through a co-design process involving local business, artists and industries, the city centre is building new public realms, new landmarks and entries, a new visitor centre and organising concurrent event and cultural activities to support the activated public spaces.

Gladstone CBD Strategy: Bonuses for planning development to reinforce an active public realm.

Gladstone CBD Way Finding Strategy: Landmarks and Civic entries reinforce the community’s vision of their sense of place in a contemporary way.

Conclusion

We have to try new ways of achieving an interactive planning and design process, because ‘it is the constant building of a thinking in which to dwell, and upon which dwelling depends’ (Heidegger, 1975) that will move us toward a more sustaining placemaking. This requires us to actively collaborate and to become ‘virtual dwellers’ through the design process.

To build a long-term cultural realm through our landscape architectural projects, we need to couple a change in design process with a change in the design content of our work. Meaningful places with sociable communities don’t happen by accident: they are created by people with purpose and conviction. At a time when market forces and global security concerns are increasingly limiting the ‘public’ and the ‘cultural’ in our cities, there has never been a more important moment for the landscape architect to become a real change-agent in the urban fabric of our cities.

References

Ellyard, P. (2001). Ideas for the New Millennium. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1975). Poetry, Language, Thought! USA: Harper & Row.

Sandercock L. (2003). Mongrel Cities in the 21st Century. London: Continuum Press.

Eisenstein,W (2004). Landscape Review: That Others May Simply Live: Ecological Design as Environmental Justice, New Zealand: Landscape Architecture Group.

Steinitz, C. (2004). Landscape Review : The Globalisation of Landscape Planning, New Zealand: Landscape Architecture Group.

Notes

¹ Carl Steinitz refers to regional landscape planning as a balancing concept, allowing risk taking in the straddling of local, national and the global. ² Sandercock imagines the development of city songlines where the language of memory, desire and spirit enter the conventional town planning process.